After returning to Bangkok, KCKP was my main project and remained so for the next five years except for some short intervals. Pasuk was busier, so I did more of the first stage of translation myself. We reached the final page on 21 January 2006. This first stage had taken fifteen months.

As we went along, we had been collecting a list of words, lines, and longer passages that we could not translate. The list had almost a thousand items. Words that don’t appear in dictionaries. Idiomatic phrases that have been lost. Astrological calculation and other forms of prediction. Textiles that are no longer known. Local names for plants, different from the current standard versions. References to literary works that are obscure or lost. Places that nobody had identified. Curses and endearments that have gone out of fashion. Food dishes, children’s games, weaponry, and a host of other articles that no longer figure in today’s world and are not defined in standard reference works.

One reason why rather few Thai read KCKP today is that there are many words they don’t know, many things they don’t recognize, and no annotated, critical edition to help them.

We aimed to translate everything so we had to understand everything. As we worked through this list, it became clear that we would have to annotate quite heavily. Initially I had hoped for an uncluttered text. Fitzgerald’s translations from Greek have no notes at all. Tyler’s Genji averages only a couple of short notes per page. But both rely on readers having quite some background knowledge—knowing what an amphora is or a kimono. Old Siam is more arcane, even to a present-day Thai.

Part way through our Kyoto sojourn, a friend brought us the newly published Matichon dictionary of Thai. This helped a lot. The Royal Institute (RI) dictionary, especially the last (1999) version, is too bulky to handle and so badly bound it soon falls apart. The Matichon has simply copied many of its entries from RI but is much better to use—printed on special paper for lightness, and bound well. Besides, some of the Matichon’s team of compilers were clearly KCKP fans. Many times when looking up an obscure word, missing from RI, Matichon would not only have the word but also have the same line from KCKP as part of the dictionary entry.

A few words we found only in McFarland or Pallegoix. Whenever the context suggested a word might have shifted in meaning, we would consult Pallegoix, especially for political terms which have often changed in meaning with the transition from traditional to modern political forms. Some obscure words we found only in the KCKP commentaries. Khun Wichitmatra in particular explained many lost terms which we have not found explained elsewhere.

After our return to Bangkok, we started acquiring specialist dictionaries. Mon, Lao, and northern Thai. Nopporn’s dictionaries of cursing and obscenity. Several dictionaries of Buddhist terminology.

Much later, I acquired a Pallegoix. I think of it as a parting gift from Professor Yoneo Ishii. I had had no idea that the Education Ministry had published a facsimile in 1999 to mark the king’s sixth cycle. I had never seen this edition in any library. After joining the memorial event for Professor Ishii at Wat Boworniwet on 5 March 2010, I dropped by the nearby Khurusapha bookshop on Rajadamnoen. Just as I was leaving, a large dusty volume caught me eye. Someone must have found a copy of the Pallegoix facsimile edition moldering in a storeroom, and decided to put it on the shelf at a discount (800 baht, I think). Had it not been for Professor Ishii’s memorial event, I would not have visited the Khurusapha bookshop around then.

I also spent a lot of time in libraries—the Siam Society, National Library, and Prince Damrong’s Library on Lan Luang Road. I went almost page-by-page through the eight thousand pages of the massive Saranukrom watthanatham thai (Thai cultural encyclopaedia) published by Siam Commercial Bank, 1994, turning up explanations of many household objects, ritual gear, dress, children’s games, and other matters. I read rather randomly in the late nineteenth century writings by King Chulalongkorn, Prince Damrong, and others when they were discovering their own country, traveling around and recording all sorts of things they found.

In November 2005 Pasuk was invited to the University of Washington in Seattle, and I spent most of the time in its library. Biff Keyes tipped me to read Robert Textor’s 1960 thesis which is probably the best account in English of supernatural objects and beliefs in central Siam.

We also made a trip to Cambridge, UK, where the library is splendidly familiar from student days. It has rather little on Thailand but I read more broadly in Indic/Buddhist studies and began to get a better idea of where the Thai traditions of supernaturalism had come from.

For the difficult botanical terms we got special help. We took our queries list on a trip to Doi Mon Lan in Chiang Mai and got help from Weerachai Nanakorn, Thawatchai Wongprasert, and Prachaya Srisanga in return for beer.

Much too late in the day, we got help from Acharn Niyada Laosunthorn. The initial contact was a little unnerving. We had written some articles in Thai on KCKP in the magazine Silapa Wattanatham (Art and Culture), and appended a list of queries on difficult words and phrases. Meting Pasuk at a research conference, Acharn Niyada told Pasuk off for soliciting help in a way which was “not Thai.” In fact this was her way of offering to help.

A couple of weeks later, we visited her home in Pattanakarn, clutching our list of remaining queries, now whittled down to a handful of pages. Over three decades of research and reading, Acharn Niyada had been compiling a dictionary of obscure words in Thai literature. The manuscript of this great work was distributed in piles around her living room. We would sing out a word, and Acharn Niyada would make for the appropriate pile—D towards the kitchen, M around the front door, and S under the stairs. Our remaining list shrank dramatically in a couple of hours.

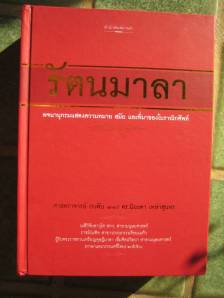

Acharn Niyada also identified a literary work, referenced in KCKP, but not listed in any literary reference work and unknown to several literary professors that we had consulted. Acharn Niyada knew that the literary work itself had been lost, but its existence was known from an early nineteenth century text. Scrambling around the bookshelves in her front room, she found a reprint of the text. Over following weeks, she answered a host of follow-up questions by phone. Her marvelous dictionary of old words is now published under the title รัตนมาลา (Rattanamala, A garland of jewels).

Twice we went to consult Sujit Wongthes. On the second occasion, he gathered a group of young acharns who helped in many ways. Both times, Sujit impressed on us that when all other routes had been exhausted, we should consult Acharn Lom.

Lom Pengkaeo is a type that recurs in Thai tradition—a teacher and extraordinary auto-didact who seems fated to fall foul of authority. He now lives in retirement. We met him in the office of a printer and publisher in Phetburi. It was a bit like consulting an encyclopedia. In a couple of hours, the list dwindled to almost nothing. Our last query concerned a line about an astrological state. We already had three interpretations of this line, mutually conflicting and none quite convincing. Acharn Lom borrowed the sheet of paper with the list, turned it over, drew the conjunction of stars, and explained its import. He too answered many follow-up questions by phone in the final stages of editing.

KCKP has many lines spoken in non-Thai languages including Chinese, “Indian,” Mon, Khmer, Burmese, and Vietnamese. The authors seemed intent on displaying the cosmopolitan mix of the population. While many of these lines are stock phrases, they are slipped into the text with a tacit assumption that readers-listeners will understand them.

By far the largest number of these foreign-language insertions are in Mon or Chinese. For the Mon, we first approached a lady acharn expert on Mon and a Mon abbot (reached through an intermediary). The results were not very convincing. Later we found Ong Bunjan and discovered why. Most of the Mon interjections are curses and obscenities.

In KCKP, the Mon are portrayed rather as the Irish once figured in English popular culture—as economic migrants in menial jobs, foul-mouthed, and the butt of jokes. Ong Bunjan is a young scholar and writer. We met him where he stays in Wat Chana Songkhram, a wat with strong Mon associations. Many of the Mon phrases in KCKP are simple curses and obscenities. A few longer ones are more difficult to decode. The Mon is rendered phonetically into Thai. There are conflicting opinions among Mon scholars on what the original was. We had to choose the version which sounded most likely, and give the alternatives in the footnotes.

The Chinese proved unexpectedly difficult. We have many Sino-Thai scholar-friend so we expected no problem. We consulted a handful of them. Their answers were not quite consistent, and two phrases which recur several times defeated all of them. That made me puzzled and suspicious. If these phrases recur in different parts of KCKP, you’d expect they were stock phrases, heard in everyday street talk, and identifying the speaker as Chinese.

It took a long time for the penny to drop. Since the late eighteenth century, the vast majority of Chinese migrants to Thailand have been Taechiu. So were all our consultants. But in the Ayutthaya era, the overwhelming majority of resident Chinese were Hokkien. When we consulted our Penang friends, Khoo Boo Teik and Tan Pek Leng, they could translate the phrases immediately.

One line of “Tavoyan” also was problematic. As Tavoy is in a Mon region of Burma and Mon figure so much in KCKP, we imagined this was a local dialect of Mon. But none of our Mon consultants would even attempt a translation. In passing, I mentioned this to Jacques Leider at a meeting in the beautiful old EFEO building in Chiang Mai. He replied immediately that it was probably Burmese, that the Tavoyan dialect of Burmese had preserved ancient forms lost in modern Burmese, and that the EFEO expert deciphering old Burmese manuscripts would probably be able to help. Indeed he could, without much trouble at all.